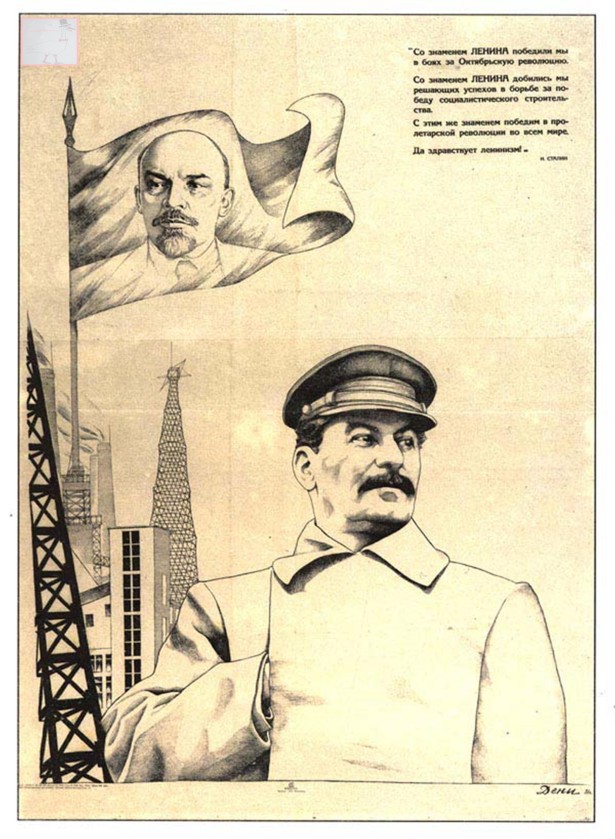

Viktor Deni (дени, B. – Виктор Николаевич Денисов), With the banner of Lenin… (со знаменем ленина…), 1931

Stalin poster of the week is a weekly excursion into the fascinating world of propaganda posters of Iosif Stalin, leader of the USSR from 1929 until his death in 1953.

Here, Anita Pisch will showcase some of the most interesting Stalin posters, based on extensive research in the archives of the Russian State Library, and analyse what makes these images such successful propaganda.

Anita’s new, fully illustrated book, The personality cult of Stalin in Soviet posters, 1929 -1953, published by ANU Press, is available for free download here, and can also be purchased in hard copy from ANU Press.

Viktor Deni’s distinctive drawing style is already well established in this 1931 poster in which the apotheosised Lenin is called on to legitimate Stalin’s rule.

Deni was one of the major agitprop artists from the beginning of the Soviet Union in 1917, right through to the end of the Great Patriotic War and his death in 1946.

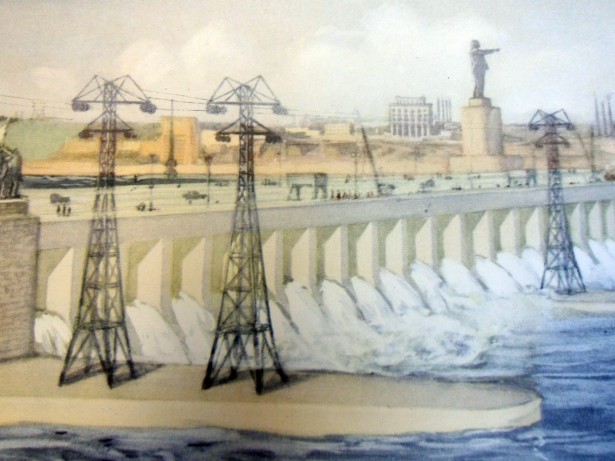

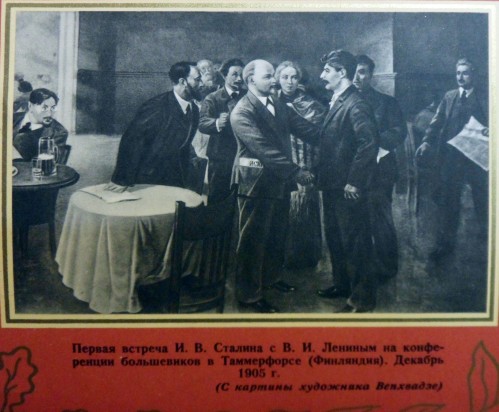

While in this poster Stalin’s image dominates the picture plane, Stalin and the scenes of construction behind him are watched over by the banner of Lenin, which is the subject of the poster’s text. In these early years of Stalin’s leadership, Lenin was continually referenced as the Party’s charismatic founder, as an ideological authority, and as a legitimator of his successor to the Party leadership.

The banner of Lenin is inspirational, protective and intercessionary for both Stalin and the Soviet people

Lenin, in characteristic collar and tie (a white-collar intellectual) looks slightly to the left, signifying his association with the Party’s past.

The poster caption invokes the protective and inspirational function of the Lenin banner, as well as stressing the military metaphor of the ongoing battles in the quest to achieve socialism:

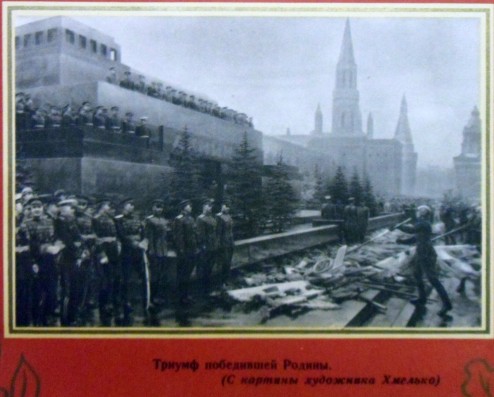

With the banner of Lenin we were victorious in the battle for the October revolution.

With the banner of Lenin we were victorious in attaining decisive achievements in the struggle to build socialism.

With the same banner we will be victorious in our proletarian revolution throughout the world.

Long live Leninism.

This text quotes Stalin from the Political Report of the Central Committee of the XVIth Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union CPSU (b) on June 27, 1930 in which he discusses the world economic crisis and capitalism in decline, contrasting it with socialist success and growth.

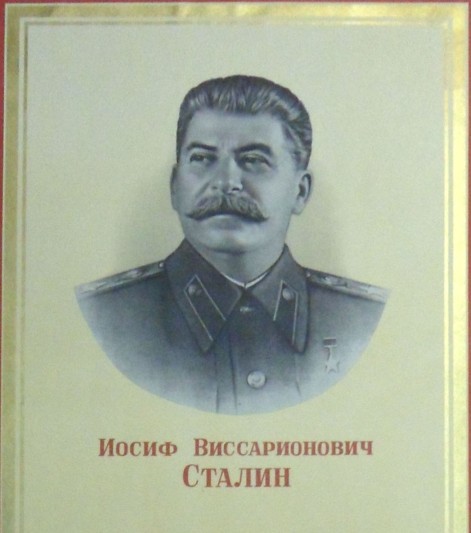

Deni depicts Stalin in a typical ‘hand-in’ pose, signifying ‘boldness tempered with modesty’

Stalin appears in the poster as steely and determined, his head turned to the right – the direction of the future. Stalin is depicted with his hand in his jacket, in what the English-speaking world refers to as the ‘Napoleonic pose’.

Stalin sometimes adopted this pose in media photographs, which suggests that perhaps this was habitual or comfortable for him. While portrait painters and poster artists may have been copying nature when presenting Stalin in this manner, the prevalence of this gesture in images of him in the media suggests that it conveyed a specific meaning.

Unlike in the English-speaking world, the gesture is not interpreted as ‘Napoleonic’ in Russia, and it makes little intuitive sense for Stalin to copy a gesture associated with Napoleon.

In fact, as Arline Meyer* notes, the ‘hand-in-waistcoat’ pose is encountered with relentless frequency in 18th-century English portraiture, possibly both because it was a habitual stance of men of breeding and because of the influence of classical statuary (Stalin frequently adopts this pose in statues).

Meyer traces classical references to the ‘hand withdrawn’ back to the actor, orator, and founder of a school of rhetoric, Aeschines of Macedon (390–331 BC), who claimed that speaking with the arm outside the cloak was considered ill-mannered.

The gesture is discussed as a classical rhetorical gesture by John Bulwer** in 1644 and by François Nivelon*** in 1737. Nivelon states that the ‘hand-in-waistcoat’ pose signifies ‘boldness tempered with modesty’, and Bulwer notes that ‘the hand restrained and kept in is an argument of modesty, and frugal pronunciation, a still and quiet action suitable to a mild and remiss declamation’.

Stalin took pride in his mild, anti-oratorical mode of speech. A reading of this gesture that suggests ‘boldness tempered with modesty’ is in keeping with the persona created for Stalin in Soviet propaganda.

*Arline Meyer, ‘Re-dressing classical statuary: the eighteenth-century “hand-in-waistcoat” portrait’, The Art Bulletin, 77, 1995, pp. 45–64.

**See John Bulwer’s double essay ‘Chirologia, the natural language of the hand’, and ‘Chironomia, the art of manual rhetoric’, in Chirologia: or the naturall language of the hand. Composed of the speaking motions, and discoursing gestures thereof. Whereunto is added Chironomia: or, the art of manuall rhetoricke. Consisting of the naturall expressions, digested by art in the hand, as the chiefest instrument of eloquence, London, Thomas Harper, 1644.

***François Nivelon, The rudiments of genteel behaviour, 1737.

Anita Pisch‘s new book, The personality cult of Stalin in Soviet posters, 1929 – 1953, is now available for free download through ANU Press open access, or to purchase in hard copy for $83. This lavishly illustrated book, featuring reproductions of over 130 posters, examines the way in which Stalin’s image in posters, symbolising the Bolshevik Party, the USSR state, and Bolshevik values and ideology, was used to create legitimacy for the Bolshevik government, to mobilise the population to make great sacrifices in order to industrialise and collectivise rapidly, and later to win the war, and to foster the development of a new type of Soviet person in a new utopian world.

Dr Anita Pisch’s website is at www.anitapisch.com