Although zines were proclaimed dead in the 1990s, this labour-intensive, anti-technological art form has not disappeared. Today, we live in the golden age of zines, with a proliferation of zine fairs and workshops, zine collections in public libraries and galleries, and thriving distros (distributors), both bricks-and-mortar and online.

Anita Pisch explores what keeps this subversive counter-culture fresh and immune to hijack by the mainstream?

The anarchic do-it-yourself ethos of zine culture subverts the values of mass-produced, commercially controlled, globally marketed publishing.

Zine workshop image from Barnard Library Zine Collection.

Some rights reserved

Everything old is new again

In the publishing world today, there is constant hype about the ‘death of the book’ and the imminent extinction of printed matter in general. Zines occupy a paradoxical position. Handcrafted using antiquated technologies, swapped or sold at cost-recovery prices, they embrace the personal and particular, the quirky and queer, the off-beat and even the off-putting.

As a form of self-publishing, zines show huge diversity of form and content, but can generally be described as adopting positions that are ‘in opposition’ to both mainstream culture and mainstream publishing. Zines depict, in sharp relief, what mainstream commercial publishing excludes.

In contrast to the publishing industry, including desktop, ebooks and self-publishing, zines carve out a niche that rejects those technologies, commercialisation and the attached audiences and markets.

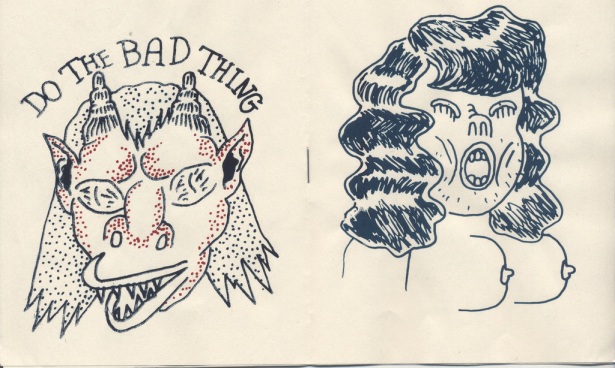

Pages from silk-screened zine Tat Squad by Will Laren. Some rights reserved.

Zines are not blogs!

One reason given for the death of the zine is the flourishing of the internet, which gives almost everyone the ability to create personal websites and blogs. Those who prophesied the death of the zine at the end of the 1990s, saw blogs and ezines as the probable replacements.

But zines are not blogs.

Blogs

- seem to be self-published, but are usually hosted by an ISP with the power to pull the piece

- require access to computers and the internet, excluding the poor and remote

- are largely confined to linear formats, using templates from an outside provider

The world wide web is a big wild world, and many bloggers have not been met with the gentle support, tolerance and understanding that characterises the world of the zinester.

Zines can’t be hacked and don’t attract the sort of public trolling or abusive commentary that the anonymity of message boards and forums on the web encourages. In order to vilify a zinester, you have to go to the trouble of writing a letter and posting it, or to creating your own zine as a response.

The early 1990s saw the flourishing of the Riot Grrrl movement and third wave feminism, which both adopted the zine form to give voice to women’s (and third wave girls’) perspectives which were largely absent from mainstream media.

Gone Home zine.

Photo by Steve Gaynor, The Fullbright Company. No rights reserved

Misfit zinesters

Mainstream capitalist culture polarises people into winners – people who can blend in, negotiate the system, gain permanent employment, and consume – and losers – people who appear or behave differently to the norm, undertake menial or itinerant work, struggle to jump through Centrelink’s hoops, are poorly networked, and who, through choice or circumstance, fail to consume.

The idea that zines are produced by social misfits simply to prove that they are not alone, has a kernel of truth. To survive, zines partake of street culture which, by necessity, is secretive and carries an element of risk or stigma. Within the DIY ethos, zine culture incorporates elements like

- slacking (defying consumerism by avoiding paying)

- scamming (especially employers’ time and materials to produce zines)

- and dumpster diving

Australian youth are often labelled in the media as apathetic, lacking commitment, irresponsible, delinquent and even criminal, and are denied access to the means of production of mainstream culture and media. Zine production strikes back at this negativity by exhibiting passion, commitment, energy and undeniable cultural and political awareness as a valid base from which to reject the mainstream.

In Australia, zines have also provided a forum for marginalised groups such as the refugees detained at the Villawood Detention Centre in Sydney, with their zines distributed online and through distros nationally, including the Sticky Institute in Melbourne.

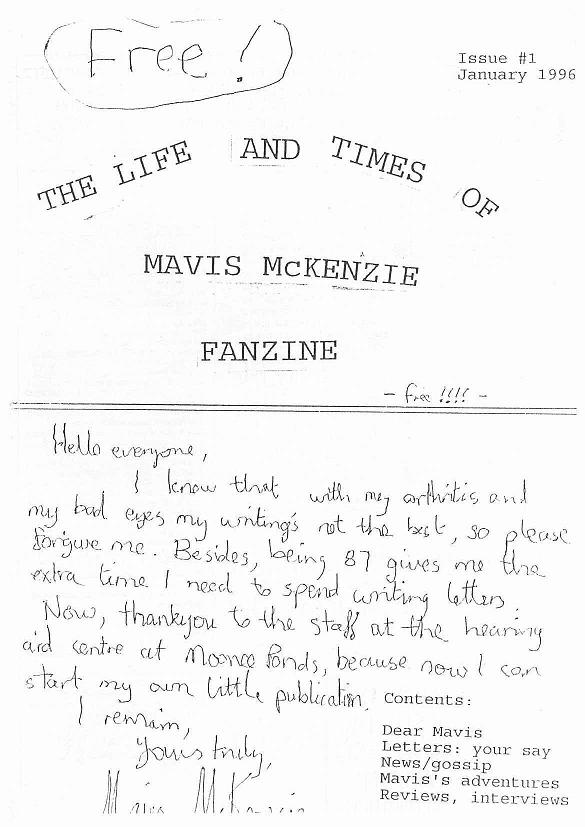

Classic zine The Life and Times of Mavis McKenzie (1996 -), held in the zine collection of the National Library of Australia. ‘Jason’ poses as Mavis McKenzie, an elderly woman who writes ridiculous letters to public figures and institutions, often eliciting hilarious responses.

Image from ZineWiki. No rights reserved

Going mainstream?

Zines now form part of the holdings of major libraries and public institutions and are heralded by some as key primary source material for historians of the future from which to analyse and document our times.

John Stevens from the State Library of Victoria talks about the unique qualities of zines and the SLV zine collection. Youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fccGYdLVqsk. Published on 22 Nov 2015.

Zine fairs are held at many prominent cultural institutions, including the Museum of Contemporary Art (the biggest zine fair in the Southern Hemisphere), the National Gallery of Victoria, the National Gallery of Australia and various state libraries. In 2016, major zine events included the Sticky Festival of the Photocopier, Feb 2016, and the MCA Zine Fair, June 2016.

There are zine workshops and events at Melbourne’s Emerging Writers’ Festival, Newcastle’s This Is Not Art and the National Young Writers’ Festival, and dedicated distros in five Australian capital cities:

- Sticky Institute – Melbourne

- Paper Cuts Collective – Brisbane

- Take Care – Sydney

- Aunty Mabel’s – Perth

- Co-West – Adelaide.

Since opening in 2001, the Sticky Institute alone has stocked over 11,000 titles (including overseas zines). Although gaining some mainstream recognition by scholars and librarians, zines will no doubt continue to flourish in their subversive, slightly subterranean counter-cultural existence, perpetually evolving to occupy the fringes.