Viktor Koretskii (Корецкий, Bиктор), On the joyous day of liberation from under the yoke of the German invaders the first words of boundless gratitude and love of the Soviet people are addressed to our friend and father Comrade Stalin – the organiser of our struggle for the liberation and independence of our homeland (В радостный день освобождения из под ига немецких захватчиков первые слова безграничной благодарности и люби советских людей обращены к нашему другу и отцу товарищу СТАЛИНУ – организатору нашей борбы за свободу и независимость нашей родины), 1943

Stalin poster of the week is a weekly excursion into the fascinating world of propaganda posters of Iosif Stalin, leader of the USSR from 1929 until his death in 1953.

Here, Anita Pisch will showcase some of the most interesting Stalin posters, based on extensive research in the archives of the Russian State Library, and analyse what makes these images such successful propaganda.

Anita’s new, fully illustrated book, The personality cult of Stalin in Soviet posters, 1929 -1953, published by ANU Press, is available for free download here, and can also be purchased in hard copy from ANU Press.

In the early years of the Great Patriotic War (Second World War), Stalin’s appearances in both the media and posters declined, possibly in order to avoid associating the leader with the disastrous decisions and their consequences of the beginning of the war. The Germans clearly had the upper hand and, at one stage, came within a few kilometres of capturing Moscow.

By 1943, with the tide of the war turning in the Soviet Union’s favour, Stalin began to appear in propaganda more frequently and was sometimes depicted as ‘standing in’ for absent fathers.

In Viktor Koretskii’s ‘On the joyous day of liberation …’ of 1943, a portrait of Stalin is hung on the wall like an Orthodox icon and has talismanic properties; however, the child is also treating the portrait as if it were a portrait of his own father.

This bearded peasant is unlikely to be the child’s father – younger men are away from home, defending the Motherland from the Germans

The peasant man in the poster appears too old to be the husband of the young woman, or father of the child, and it can be safely assumed that, with the war still raging outside the window, the child’s father is away defending the nation.

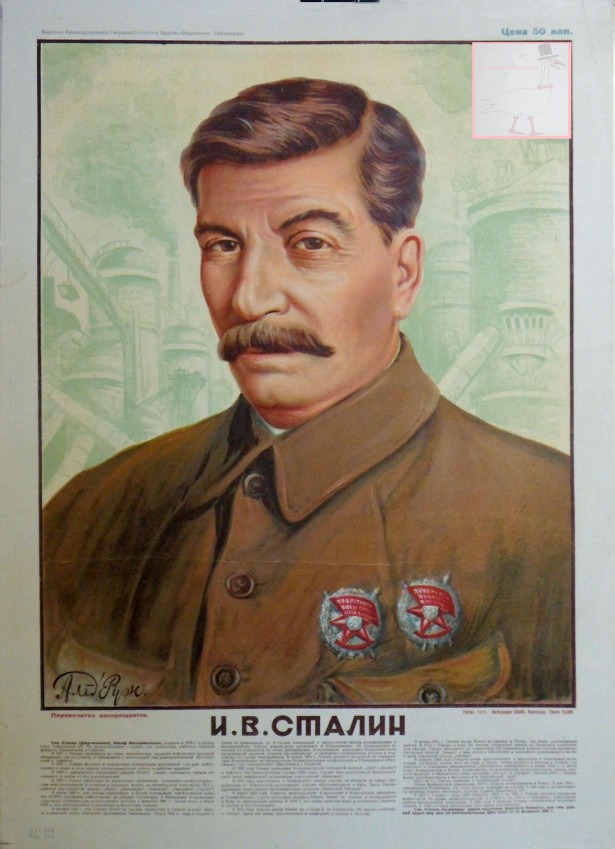

The family gather instead around a portrait of Stalin who, in this early version of the poster, is not wearing insignia of military rank and looks humble and approachable. This reading of the poster is supported by the lengthy poster caption in which Stalin is referred to as ‘our friend and father’, rather than a great warrior or military strategist.

In 1943, the USSR was gaining back some of the earlier lost ground, and claiming some victories against the German invaders. The poster lays responsibility for these victories wholly at Stalin’s feet.

Stalin’s portrait is hung on the wall like an icon

Stalin’s portrait is hung in a ‘Lenin corner’ or ‘Stalin room’ as they were now sometimes called, with great reverence by a young, blond child who appears to be instructing his peasant family in the virtues of Stalin’s beneficence.

The little Russian boy represents the future of the motherland. Stalin is the glorious father who is to be venerated above all others. As art historian Erika Wolf observes: ‘The family resembles the Holy Family, with a mother and child accompanied by an older and impotent man, akin to Saint Joseph.Stalin thus stands in as the absent father of the family, as well as the “father comrade” of the Soviet people.’*

Stalin appears soft and humble – paternal

Stalin’s portrait is soft and paternal and the icon’s talismanic powers are juxtaposed with Soviet military success. The frame of the portrait balances the window frame through which a large red flag and some departing soldiers can be seen. The Red Army soldiers have restored peace and the village is intact and safe.

Through the window can be seen the (somewhat blurry) image of troops departing under a red flag

Koretskii’s poster celebrates the liberation of an occupied village and inspires the population with hope for victory in the war. The extensive text makes it clear who is responsible for the victory, and to whom a boundless and unpayable debt of gratitude is owed:

‘On the joyous day of liberation from under the yoke of the German invaders the first words of boundless gratitude and love of the Soviet people are addressed to our friend and father Comrade Stalin — the organiser of our struggle for the liberation and independence of our homeland.’

Stalin does not yet appear in full military uniform and, despite being appointed marshal of the Soviet Union in 1943 and accepting the award of the Order of Suvorov, First Class,** in November 1943, he may still have been cautious about claiming military and strategic brilliance until ultimate victory in the war was assured.

* Erika Wolf, Koretsky: the Soviet photo poster: 1930–1984, New York, The New Press, 2012.

** The Order of Suvorov, created in July 1942, was awarded for exceptional leadership in combat operations.

Anita Pisch‘s new book, The personality cult of Stalin in Soviet posters, 1929 – 1953, is now available for free download through ANU Press open access, or to purchase in hard copy for $83. This lavishly illustrated book, featuring reproductions of over 130 posters, examines the way in which Stalin’s image in posters, symbolising the Bolshevik Party, the USSR state, and Bolshevik values and ideology, was used to create legitimacy for the Bolshevik government, to mobilise the population to make great sacrifices in order to industrialise and collectivise rapidly, and later to win the war, and to foster the development of a new type of Soviet person in a new utopian world.